san francisco

day in the life turned short story about my neighbor Phil

Everything is gray and bleak and dull. I often look back on summer 2022 because I was naïve and easily fascinated by everything. I was a child and New York was my playground. Now I feel like I’m how I saw my dad when I was little: stressed, money-hungry, and in need of constant career validation. I’m 21, but feel 45, and New York is my laptop screen, burning holes in my eyes because I’ve stared at it too long. I want to leave but I can’t because I love it.

In times like these, I like to think about my downstairs neighbor Phil, back in San Francisco. He’s pushing 90. Phil walks to Crissy Field at 7 am sharp without fail. I know this because I hear him violently slam the front door every morning. The whole apartment complex shakes and I’d wake up because he’s hard of hearing and underestimates his arm strength.

He saunters down our marble staircase one step at a time. The old owner of our flat once slipped on the same stairs after a rainy day. She hit her head and slid down the entire staircase and landed in a heap on the cement. Her skull cracked open and a pool of blood sprawled out from under her. Phil knows this, but he has his shimmery burgundy cane and his crusty white dog named Jackson as third and fourth legs, so he’s fine.

There are a few ways to get to Crissy Field. Phil takes the longer route. It’s a meandering trail through the Presidio, the type of trail that if you lose yourself on, you completely forget you’re in the middle of San Francisco. Forests of large redwood trees swallow you whole. Coyotes are as common as squirrels and sometimes chase little dogs and their owners if not careful. When it’s foggy (which is the case more days than not), a layer of misty gray lingers on the forest floor, making shrubs and branches indistinguishable from other people, other creatures. The air holds secrets.

Phil has a wife named Leslie (lawyer; red-head; aged 70) who he leaves at home while he goes on his walks. He used to fly planes in the Air Force and would often deliberately fly into a large gray plume to be out of sight from the other members of his group. Walking in the Presidio feels the same; his only company is the misty dew drops and Jackson, who happily pants next to him, his tongue lolling out of his mouth.

He cries to himself on these walks. He doesn’t bawl, for fear of attracting unwelcome creatures; he silently lets tears roll out of his eyes. They rhythmically stream down his face and onto the ground every few steps he takes. He’s not sure why this happens. It’s as though his tear ducts have an internal clock that’s automated to release their floodgates every time he hears the gentle rush of El Polin Spring, or every time he passes the wooden bench in the dead center of looming Redwoods. Phil loves this bench because it looks like something he’d make in his garage. Planks of chopped wood are messily nailed together. There’s a golden plaque that says In memory of Doña Juana Briones de Miranda (1802-1889) on its backside. Phil doesn’t know who she was, but he likes to imagine she watches over the Presidio, makes sure the city doesn’t let the crazies in. Another tear rolls down his cheek and disappears into the forest floor.

He never cries at home, not when Leslie is there, not when he sits on the couch reading the newspaper only to look up and see china tea sets and porcelain dolls lining every glass encased shelf in the living room. When their grandfather clock strikes 6, he shuffles into the kitchen for dinner. Leslie probably made chicken pot pie, steamed green beans, lasagna of some sort. She’d talk about neighborhood drama – Julia Roberts moved out, the Matthews are still in Spain, the construction next door is too loud. Phil would grunt in reply, eat his dinner, and shuffle into the basement to finish building his model airplanes.

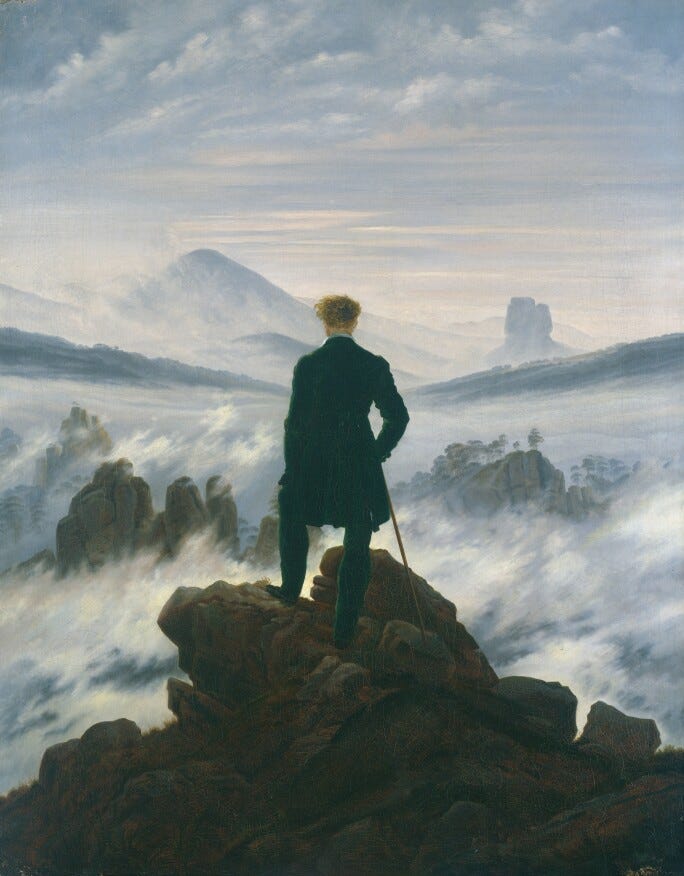

Phil emerges from the forest and into the Main Post, a sprawling green lawn that stretches the length of a typical street block. Up here, at the top of Main Post, where he can see the green lawn, the Bay, the bridge, the hills of Marin, he likes to pretend he’s in a Caspar David Friedrich painting, has reached the summit of a mountain, with his cane, watching the world unfold before him. A blast of wind carrying salty ocean mist slams his face. He breathes in deeply. If he could paint, he would paint this scene on a large canvas to permanently capture its 7 am stillness, its untainted beauty. He’d hang it above his fireplace mantle, next to Leslie’s china tea sets and porcelain dolls.

He continues walking down Main Post, past the Tunnel Tops, over the 101 bridge, and finally onto Crissy Field. The Golden Gate Bridge looms grandly before him. He unclips Jackson’s leash. Jackson sprints onto the sand, then onto the adjacent green lawn, and finally into the gray nothingness. Phil smiles. Jackson will come back.

It’s winter so there have been lots of rainstorms and the waves are violent. The ocean retracts, inhales, revs up for the big swell, then releases, exhales, harshly slams onto Crissy Field’s shore, sending a large boom into the atmosphere like a million cannonballs firing simultaneously. Phil sets up his chair on the beach. He takes pride in the fact that the chair isn’t a piece of tarp upheld by dingy metal poles that go for $50 at REI. His chair is covered in royal blue fabric, supported by smooth golden poles elegantly extending from each chair leg's rivet. Engraved on the side chair leg reads All my best, Daniel. Daniel flew with Phil in the Air Force and gave him the chair as a retirement gift. He died in a plane crash two days later. Nothing was recovered; they say he hit the side of a mountain and burst into a fiery explosion. When Leslie packs their Volkswagen for beach days up north, Phil scolds her if she carelessly throws it in the trunk. He can’t go to the beach without it.

Jackson bounds out of the gray suddenly, tongue flying in the wind, fur wet with morning dew and ocean. He looks like he’s smiling. He halts at Phil’s chair and shakes himself dry, wetting Phil in the process. Phil gently pets him. They both serenely stare into the ocean as it continues rhythmically recoiling then pounding the sand, recoiling then pounding, recoiling then pounding. This is the same ocean that gently rolls onto white sand beaches in Hawaii; the same one that dramatically shimmers from the passenger’s side window as you speed down the PCH into Malibu. But Phil likes how in San Francisco it’s gray and wet and cold. He likes how it doesn’t change for the gawking tourists or align itself with the pastel rainbow of Edwardian façades that litter the city. It forcefully claws its talons onto the shore, piercing the sand’s skin until the beach draws blood and a wound is created. It has nothing to prove.

Phil smiles as he imagines being gently swept away by the white-capped waves until reaching the Farallon Islands. He’d stare out at his city twinkling through the gray, and breathe his last breath, content, listening to the ocean fire its cannonballs. San Francisco would be the last thing he’d see.

I hope to die in San Francisco. I’ll think of Phil when I do.